Cineblatz

As strenuously obsessive about his work as Harry Smith, Brighton-based Jeff Keen was an important figure on the British underground scene of happenings and “expanded cinema”. But wider acclaim arrived only late in his career and life. Keen’s health was failing by the time his films were gathered by the British Film Institute for the 4-disc DVD Gazwrx and retrospectives like 2012’s Gazapocalypse were staged. Around the same time his equally mad music - made using processed shortwave radio sounds and other electronic effects got released by Trunk Recordings under the title Noise Art.

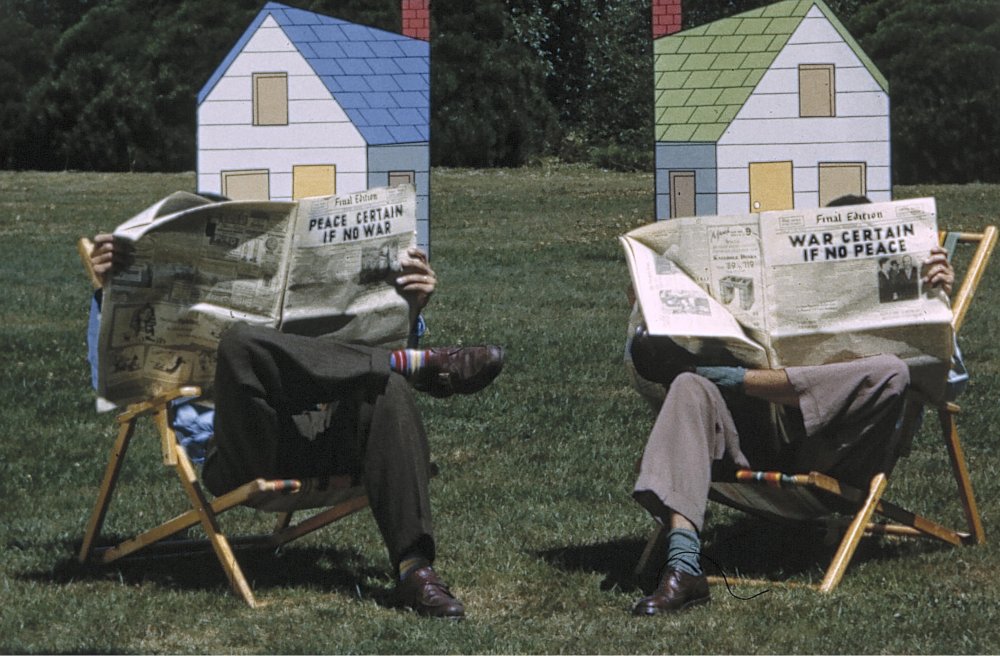

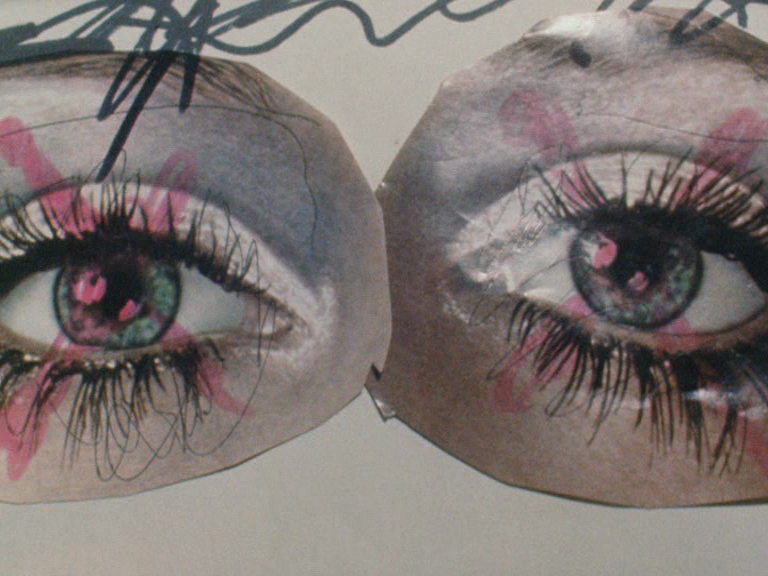

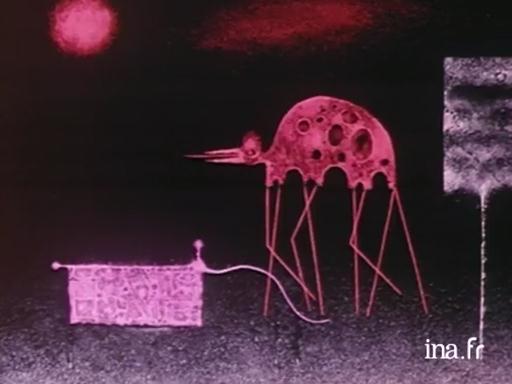

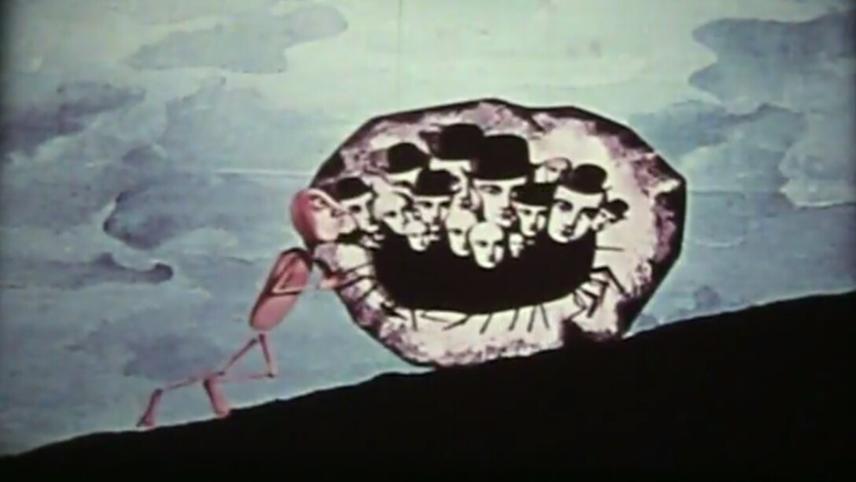

That phrase fits Keen’s films too. The strobe-like barrage of imagery impacts the eye like visual noise. “Cineblatz” (1967) is a retinal riot, a rapid-fire cacophony of scrawled drawings, roughly clipped photographs from magazine advertisements and newspaper stories, and 3D objects like the plastic toys that melt before our eyes. Violence convulses the screen: not only are there endless explosions and savage acts, but the materials out of which the film is montaged are burned black or stained with soiling splurges of colour. Like a simultaneously puerile and psychotic version of Pop Art, famous faces get defaced, mutilated, or shunted into unlikely and unsavory encounters. Keen loved pulp culture: B-movie and comic-book monsters and superheroes rub shoulders with the likes of J.F.K.

There is something vaguely pornographic about the frenzied pace of the imagery – one critic described how “the artist ejaculates ideas onto the screen faster than the eye can properly register”. Most likely that reflects the carnography of TV news in the Sixties, the battery of images of brutality and disorder. But Keen also spoke of being a young soldier during World War 2 and how being exposed to the horror and anarchic surrealism of the battlefield was a simultaneously traumatic yet strangely liberating experience.

- Simon Reynolds