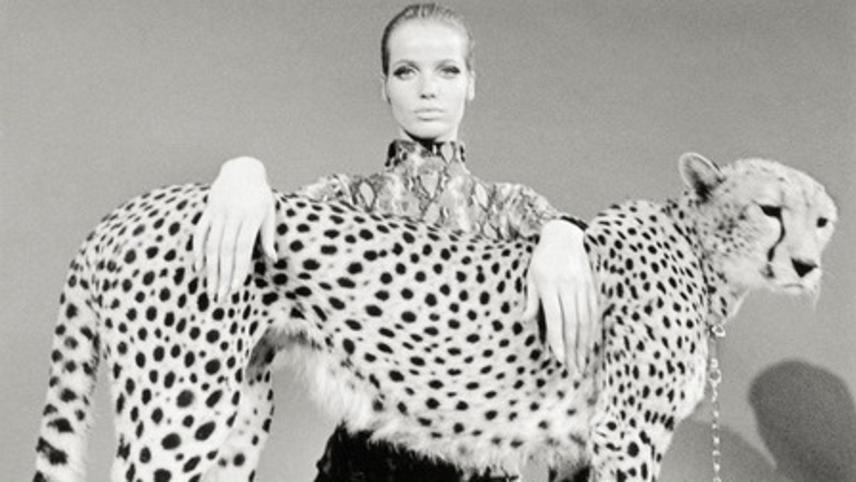

Blonde Cobra

Both Jacobs and Smith had a capacity for reuse and repetition, returning to old material – both their own, and that of others – to see what they could find in the mouldy dustbins of history. Repetition became particularly important when Jacobs moved toward structural film, with his 1969 film, Tom Tom The Piper’s Son, a masterpiece of the genre. (Structural film, an important movement in 1970s experimental film, focuses on the form and structure of film itself, rather than narrative, plot, and other, similar devices.) But on Blonde Cobra, which Jacobs edited together in 1963 from discarded material recorded by Smith and fellow film maker Bob Fleischner, Jacobs plays with structure in altogether different ways. Failure was part of the aesthetic that these film makers were exploring, and Blonde Cobra is a film that seems to fall apart before your very eyes – or that seems to fall apart, consciously reconstitute itself, and then slowly collapse again. There’s a strong psychodramatic element to the film, thanks to the improvised, stream-of-consciousness rambling from Smith that Jacobs folds into the film – this rambling often only appears when the screen is black, no visuals to focus on. The film’s despairing tenor is sometimes undercut, though, with mordant humour. The whole thing is summed up by Smith’s quote from French poet Charles Baudelaire, which also appears in Little Stabs At Happiness – “Life swarms with innocent monsters” – and these films would come to be understood as exemplars of a kind of ‘Baudelairean cinema’, according to film maker and critic Jonas Mekas.

- Jon Dale