In 'Crestone', a cloud is also a horizon

SoundCloud rappers try to found a brotherly utopia in an isolated locale of Crestone, Colorado, but clouds of weed smoke and their heightened instagram personas seem to haze that grand horizon.

Where will humans go if they cannot live in the cities, towns and villages we live in now? How might we begin again? What will culture look like after the collapse of societies and the current normality? How will sounds, images, performances be recorded, and transmitted to an audience? What does music sound like if there is no one left to repost and share it?

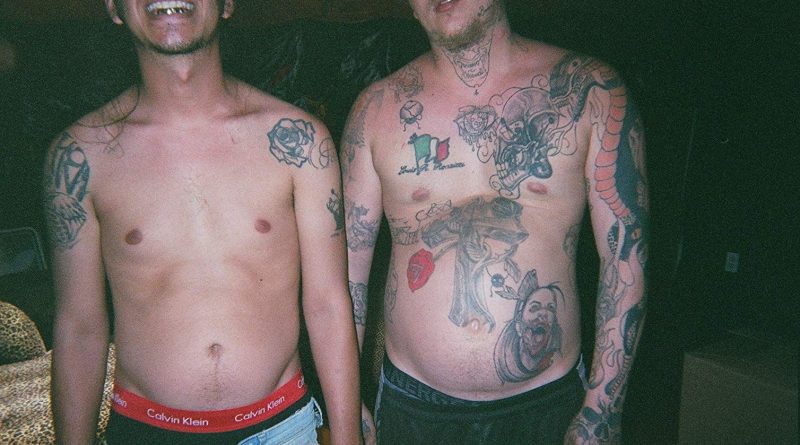

In ‘Crestone’ director Marnie Ellen Hertzler collages mixed media images and moments of soft spoken diary narration to sketch a chronicle of her visit to an old highschool friend and his precarious community of comrades. Sloppy (ChamplooSloppy) and his crew Baby Boy, Ben, Hakeem, Huckleberry and Ryan, are all SoundCloud rap boys, trying to found a brotherly utopia in the isolated locale of Crestone, Colorado, but clouds of weed smoke and their heightened instagram personas seem to haze that grand horizon and the reality that plays out before it. Their lives undulate between desert adventures and computer games, fact and fiction, digital and physical, clarity of ideals and clogginess of the quotidian.

Crestone, Colorado, is a site of occupation that if searched on Googlemaps appears as eight horizontal lines of unequal length, and fragments of four to five vertical roads; an incomplete grid for incomplete lives to unfold. Contained within this liminal space there is a post office, a shop, an Ashtanga yoga center, a voluntary fire department, a school, an artisanal gallery, a liquor center, some form of lodging, a brewing company and a cafe named The Cloud Station, perhaps a homage to a local nephologist, or Soundcloud, or the clouds of smoke exhaled by some of its occupants.

Their community is emergent, agrarian to the extent that they grow their own vice, and seemingly ill prepared for post-societal existence. Sloppy acts as the centrifuge and fundraiser for their mission to form a sustainable desert settlement. He utters egalitarian principles at the heart to their nascent world: “the rise of technology is leading to the downfall of being a true human, I just want to create a community where we can all live together and grow old, knowing we are surrounded by people who care and love each other with no judgement or negativity.” The group commonly exhales altruism and yin and yang philosophy, sometimes this manifests in throaty giggles, sometimes in deeply humanitarian thought.

Hertzler’s film was shot over eight days, and this brevity of encounter lingers after viewing: like emerging from a weekend hanging out at a poorly equipped holiday camp hut perforated with memories of minor forays into nature, crappy longlife food, and a suitcase full of your bravest outfits that are rarely seen in day to day dress code. But this is a succinct film, for all its lack in traditional narrative development, its fluid portraiture is infused with a light hearted profundity and self-reflection. The daily lives of Sloppy and his crew meander between geographical isolation and virtual omni-broadcast, rendering Crestone a performative space where cosplay is an everyday custom, and natural and digital spheres of experience hybridise as the backyard scrub becomes the set of an AR infused music video.

Just as in the present moment of reduced life activity, food scarcity and preparation become key quotidian scenes in Crestone. Pot Noodles are consumed with waterfalls of tomato ketchup, and fried baloney is prepared with a brazen dexterity reminiscent of a viral episode of Come Dine With Me in which the contestant adapted an oven glove into a universal kitchen utensil. On a group trip the rap collective rambles their way to a hillside cave, apparently once the home of a single gentleman. Hertzler emphasises the post-apocalyptic hunter-gatherer aspect of this journey, Sloppy wears a Jon Snowesque fur shoulder garment, they carry slingshot and a curved stick presumably as a form of protection from wild animals and other Mad Max marauders. However the group are clearly more acquainted with trap music than trap hunting.

The posse enter the cave appearing as post-everything neon-anderthals on a cornershop paleo diet ready to pillage abandoned edible goods. Inside the cave they encounter filthy debri of human occupation, including a coolbox which has been adapted to become a faecal depository. “It looks like a bucket from Resident Evil V” remarks one of the cohort offscreen. The cooler box is filled with wet excrement and a glass jar of crunchy peanut butter. The peanut butter is almost a real manifestation of the gems from Sonic the Hedgehog appearing in an earlier music video section of the film, emphasising the augmented reality this cast of friends inhabits. They choose not to take the coolbox challenge and leave without this bonus point of protein. Instead they forage for a jar of dried parsley, poultry seasoning, and an essential cheetah print garment, before some unknown creature briefly appears on screen as a neon puppy face filter and dramatically chases them from this not so bountiful cavern.

In her narration Hertzler describes her movie as a love-letter, but it feels more like a message to an irregular pen-friend, Facebook connection or email acquaintance, someone with a longing for understanding that will never likely be translated to IRL association. Like many people who attempted the foray of nostalgic connection spending a day or even a pint with a highschool friend, distance is quickly evidenced and past differences remembered. Hertzler grows a little weary of the novelty of this reengagement. She laments the group’s wavering responsibility in the present where “performance and being became indistinguishable”. This might also be translated to “can you hold back on the art life for a moment and just turn up on time or eat something healthy?” Perhaps their future utopia is not a viable alternative to post-societal being, but a wilful ignorance and cloudy dismissal of it: ‘if the world was ending, they probably wouldn’t even notice’.

As we may have come to know the pandemic as a portal, Sloppy views the collapse as a catalyst, “It's kinda like the world is collapsing in on itself but opening up to a new world.” There is much to escape from for this generation: the persistent precarity of modern labour, a housing market that closed and locked the front door but offered a fold-out bed in the garage with a leaking wall for more rent per month than the mortgage on the entire property, politicians who represent nobody you know, and a climate crisis set on making your descendants refugees to higher land.

Champloo Sloppy’s own realisation that days of little activity, eating baloney and chilling is not leading to a future utopia manifests from the frustration with a failed attempt to watch the movie Avatar due to a non-functional remote control. This moment of resignation mutates into a broment of togetherness, where the posse realise that their commensal relationship with each other and a harvest of marijuana is at least something to hold onto in the present.

Hertzler’s debut feature-length film is a document that at the beginning of this year would have appeared to be a portrait of peripheral figures indulging in a speculative fallacy of self-quarantine as a source of creative freedom of virtual connection. A little over a month after its real life premiere at America’s True/False film festival and a cancelled SXSW outing, the inflated resonance the film’s vision of contemporary life is evident by the very means and conditions that you are reading this article and watching ‘Crestone’ on 4:3 on 4/20. As each of us self-isolates during a pandemic, speculative communities may appear more like viable alternatives to new normality, perhaps this is the time to think about new community settlements, but can Crestone be our model?

Just as scientists of the present have studied the 5,300-year-old tattoos and dietary traces of the glacially preserved body of Ötzi to understand the travails of our ancestors, perhaps the archaeologists of the future will excavate the desert mummified stomachs and inked bodies of sadboys and emo rap clans to understand the demise of the present.